Few could anticipate that directly beneath an innocuous-looking, small, metal grill set in the pavement of an alleyway, at the side of a Betfred shop in Royston town centre is a thirty-foot drop into an ancient, mysterious cave.

Thankfully, I don’t have to wriggle through the grill in order to enter the cave itself, but the actual entrance could be just as easily missed. An anonymous doorway in Katherine’s Yard, Melbourn Street gains access to a flight of steps leading down, which in turn give way to a fairly steeply declined slope, through a low-ceilinged, rough-hewn rock tunnel. Picking up a bit of a canter down the slope, I am practically propelled into the chamber beyond. And what a strange place it is.

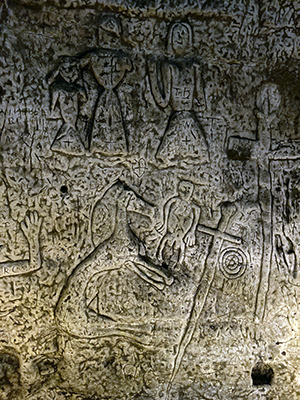

A tall, bell-shaped cave, carved from the chalk bedrock, of roughly 50-feet circumference. High above me, I can see daylight streaming through the same small grill beside Betfred, which I had stood on the other side of earlier. But, despite my apparent fascination with this grill, it is not the most interesting feature of this chamber. Not by a long chalk. On all sides of me, I am surrounded by bizarre carvings in the soft rock. They are medieval in their style; uniform and rather naïve in their execution. They adorn practically every square inch of the lower portion of the cave walls.

Some of the carvings represent clearly recognisable figures. St Christopher; St Lawrence and his griddle; St Catherine holding a spoked wheel; St George with his sword. There are King Richard I and his queen, Berengaria; Jesus and his disciples; King David, shown with upraised arms; and the last grand master of the Knights Templar, Jacques de Molay.

However, rather like the creator of the Franks Casket, the instigator of the Royston Cave carvings appears to have kept his spiritual options open: among many images devoted to Christian worship, he has inserted the pagan fertility symbol of a Sheela-na-gig.

Many theories abound regarding the origin, use and purpose of the Royston Cave. A place of worship and ritual for the Knights Templar; a possible early lodge for Freemasons during the reign of James I; an eccentric hermit’s retreat. Rather wonderfully, though, no one is sure of how it came into being. And, in uncertainty lies romance.

Most of the original artefacts found in the cave, at the time of its rediscovery in 1742, have subsequently been lost, including a human skull. Paint, which would have originally coloured the carvings, has all but been destroyed by humidity and erosion over the years, and so there is little to be able to carbon date. Does the fact that the cave exists at the intersection of two important ley lines––Michael and Mary––and two major Roman roads––the Icknield Way and Ermine Street––hold any significance?

The Royston Cave is an enigma. And that is the over-riding sensation upon visiting. The sense of mystery is palpable. It poses questions. Why? What? Who?

Why hasn’t anyone fallen through that small grill by Betfred? What would happen if they did? Who will be the first to do it?

© E. C. Glendenny

Sometimes it seems as though history is wasted on E. C. Glendenny.

Check out some of E. C. Glendenny’s other adventures underground in the Catacombs of Paris; the subterranean passages beneath Turin; and the tunnels of Heligoland.